Approximate Counting algorithms are techniques that allow us to count a large number of events using a very small amount of memory. It was invented by Robert Morris in 1977 and was published through his paper Counting large number of events in small registers. The algorithm uses probabilistic techniques to increment the counter, although it does not guarantee the exactness it does provide a fairly good estimate of the true value while inducing a minimal and yet fairly constant relative error. In this essay, we take a detailed look at Morris’ Algorithm and the math behind it.

Robert Morris, while working at Bell Laboratories, had a problem at hand; he was supposed to write a piece of code that counts a large number of events and all he had was one 8-bit counter. Since the number of events easily crossed 256, counting them was infeasible using ordinary methods and this constraint led him to build this approximate counter that instead of providing the exact count, does a pretty good job providing an approximate one.

Counting and coin flips

A very simple solution, to build an approximate counter, is to count every alternate event. In order to make the decision of whether to count an event or not - we use a coin flip, which means, every time we see a new event, we flip a coin and if it lands heads we increase the count otherwise we don’t. This way the value preset in our counter register will, on average, represent half of the total events. When we multiply the count (in the register) by 2, we get a good approximation of the actual number of events.

This coin flip based counting technique is a Binomial Distribution with parameters (n, p) where n is the total number of events seen and p is the success probability i.e. probability of getting heads during a coin flip. The expected value v in the counter register corresponding to the number of events n is given by

The standard deviation of this binomial distribution will help us find the error in our measurement i.e. value retrieved using our counter vs the actual number of the events seen. For a binomial distribution twice the standard deviation on either side of the mean covers 95% of the distribution; and we use this to find the relative and absolute error in our counter value as illustrated below.

As illustrated in the image we can say that if the counter holds the value 200, the closest approximate to the actual number of events that we can make is 2 * 200 = 400. Even though 400 might not be the actual number of events seen, we can say, with 95% confidence, that the true value lies in the range [180, 220].

With this coin flip based counter, we have actually doubled our capacity to count and have also ensured that our memory requirements stay constant. On an 8-bit register, ordinarily, we would have counted till 256, but with this counter in place, we can approximately count till 512.

This approach can be extended to count even larger numbers by changing the value of p. The absolute error observed here is small but the relative error is very high for smaller counts and hence this creates a need for a technique that has a near-constant relative error, something that is independent of n.

The Morris’ Algorithm

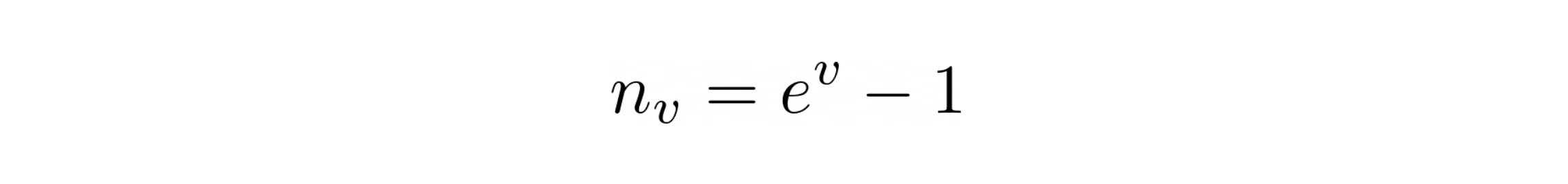

Instead of keeping track of the total number of events n or some constant multiple of n, Morris’ algorithm suggests that the value we store in the register is

Here we try to exploit the core property of logarithm - the growth of logarithmic function is inverse of the exponential - which means the value v will grow faster for the smaller values of n - providing better approximations. This ensures that the relative error is near-constant i.e. independent of n and it does not matter if the number of events is fewer or larger.

Now that we have found a function that suits the needs of a good approximate counter, it is time we define what exactly would happen to the counter when we see a new event.

Incrementing the value

Since we are building a counter, all we know is the value of the counter v and have no knowledge of the actual number of events seen. So when the new event comes in we have to decide if v needs to change or not. Given the above equation, our best estimate of n given v can be computed as

Now that we have seen a new event we want to find the new value v for the counter. This value should always, on an average, converge to n + 1 and we find it as

Since the value computed using the above method is generally not an integer, performing either round-up or round-down every time will induce a serious error in counting.

For us to determine if we should increment the value of v or not, we need to find the cost (inaccuracy) that we might incur if we made an incorrect call. We establish a heuristic that if the change in the value of n by change in v is huge, we should have a lower probability of making an increment to v and vice versa. We this define d to be reciprocal of this jump i.e. difference between n corresponding to v + 1 and v.

The value of d will always be in the interval (0, 1) . Smaller the jump between two ns larger will be the value of d and larger the jump, smaller will be the value of d. This also implies that as n grows the value of d will become smaller and smaller making it harder for us to make the change in v.

So we pick a random number r uniformly generated in the interval [0, 1) and using this random number r and previously defined d we state that if this r is less than d increase the counter v otherwise, we keep it as is. As n increases, d decreases making it tougher for the odds of pick r in the range [0, d).

The proof that the expected value of n, post this probabilistic decision, is n + 1 can be found in the paper - Counting large number of events in small registers. After tweaking some parameters and making process stabler the function that Morris came up was

When we plot values produced by Morris’ Algorithm vs the actual number of events we find that Morris’ algorithm indeed generates better approximate values to smaller values of n but as n increases the absolute error grows but the relative error remains fairly constant. The illustrations shown below describe these facts.

Python based implementation of Morris’ algorithm can be found at github.com/arpitbbhayani/morris-counter

Space Complexity

In order to count till n the Morris’ algorithm requires the counter to go up to log(n) and hence the number of bits required to count from 0 to log(n) ordinarily is log(log(n)) and hence we say that the space complexity of this technique is O(log log n). Morris’ algorithm thus provides a very efficient way to manage cardinalities where we can afford to have approximations.